A monument to the victims of the 1961 Interdiction is long overdue. But it should occupy a public space

And likewise, so is a national monument to Daphne Caruana Galizia...

There should be a monument to Daphne Caruana Galizia, the journalist assassinated in 2017 by a politically-linked mafia. There should also be a monument to the victims and events of the 1961 Church interdiction in Malta, which ‘sent Labour voters to hell’ with the indiscriminate power of sin, shame and humiliation.

But it absolutely makes no sense to erect the latter inside Church-owned property. Both must be in full view of the public.

I find it strange that Jason Micallef, one-time Labour secretary-general to Alfred Sant, is using his political voice to demand that the site for such a monument be the gardens of the Archbishop’s Palace in Valletta, where the Curia currently hosts its ecclesiastical tribunals. Such a monument should not be ‘privatised’ into a walled enclosure that is actually owned by the Catholic archdiocese. Monuments should be national sites of reflection, for all citizens – to me this sounds like a disingenuous provocation, to rile up Labour voters and for the Church to dig its heels in.

I have followed the saga in GWU organ It-Torċa, and from the outset, I will say that my ancestor, Guże Ellul Mercer, was buried on unconsecrated ground under the horrific 1961 interdiction from thug-in-chief Michael Gonzi; and I certainly do not bat for any faith, least of all the Maltese Catholic archdiocese.

If anything, I am disappointed that the Labour administration has not kick-started the process to have a monument, prominently situated along a major walkway, that marks the victims of the 1960s interdiction; as well as a decorous interpretation for the graves at the ‘Miżbla’, the moniker for the once-unconsecrated part of the cemetery that people like Ellul Mercer were buried in.

Because my fear is that the historical effects of the Gonzi interdiction will only be reduced to this enduring image of abuse of power – the truth is that not just their relatives suffered the humiliation of such a violent act of shunning; countless others faced the silent opprobrium of the clerical class by their refusal to administer the sacraments, specifically for being Labour voters, denied the grace of their faith at so many rites of passage, even denied ‘the passage to heaven...’

Read later: The Unholy War: a five-part series on Malta’s Interdett

History first...

First, a generous portion of history to explain the importance of this monument, with the help of author Sergio Grech’s Ph.D dissertation ‘Archbishop Michael Gonzi in a Changing Malta’.

The clerical activism of the late 1950s and 1960s in Malta was fuelled by a junta of Catholic organisations (il-Ġunta) which heeded the call from the Maltese archbishop to prevent Labour from “relegating the church to the sacristy”. (In Apri 1958, colonial power had been restored after the resignation of the Mintoff administration in the wake of mass dismissals at the naval dockyard, as well as the inconclusive integration referendum marked by mass abstention from the Nationalist Party and the Church’s opposition).

Archbishop Gonzi was fixated that Dom Mintoff had evolved into a socialist baby-eater from his days as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, through his membership of the Fabian Society; he saw in Mintoff the single-minded enemy who would drain his church of its earthly powers, whether by proposing integration with Great Britain, or by using class conflict and central economic planning (for this, I recommend the interviews collected by Claire Xuereb Grech in L-Elf Lewn Ta’ Mintoff, SKS).

After the failure of integration, Mintoff shifted gear for full independence, now the Maltese political mainstream’s main political goal, give or take a few variances (the Nationalist Party wanted Dominion Status like Canada or Australia). And here came the straw that broke the camel’s back for Gonzi. Labour declared in a new policy statement that independence meant Malta would not turn its back on any outside assistance (that is, West or East) and accused Gonzi of being interested only in his diplomatic relations with the Vatican and the United Kingdom (whatever kept him in absolute power as princeling).

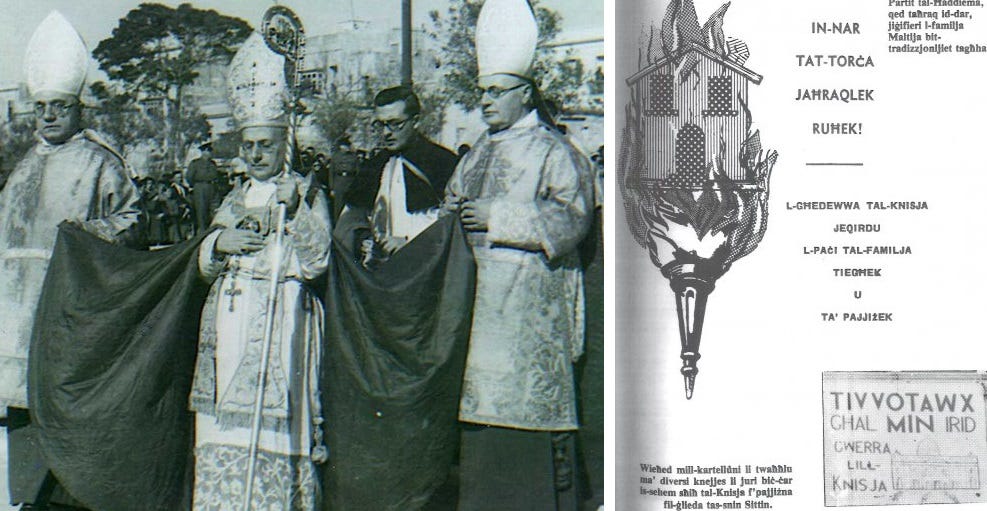

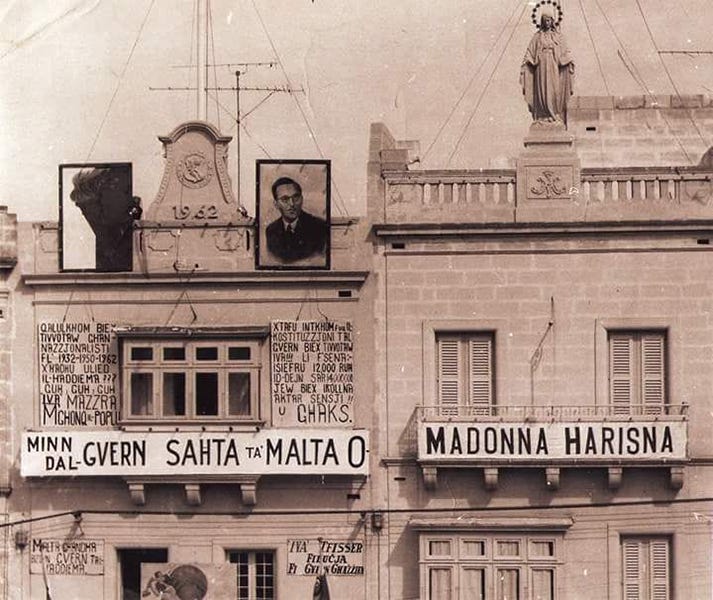

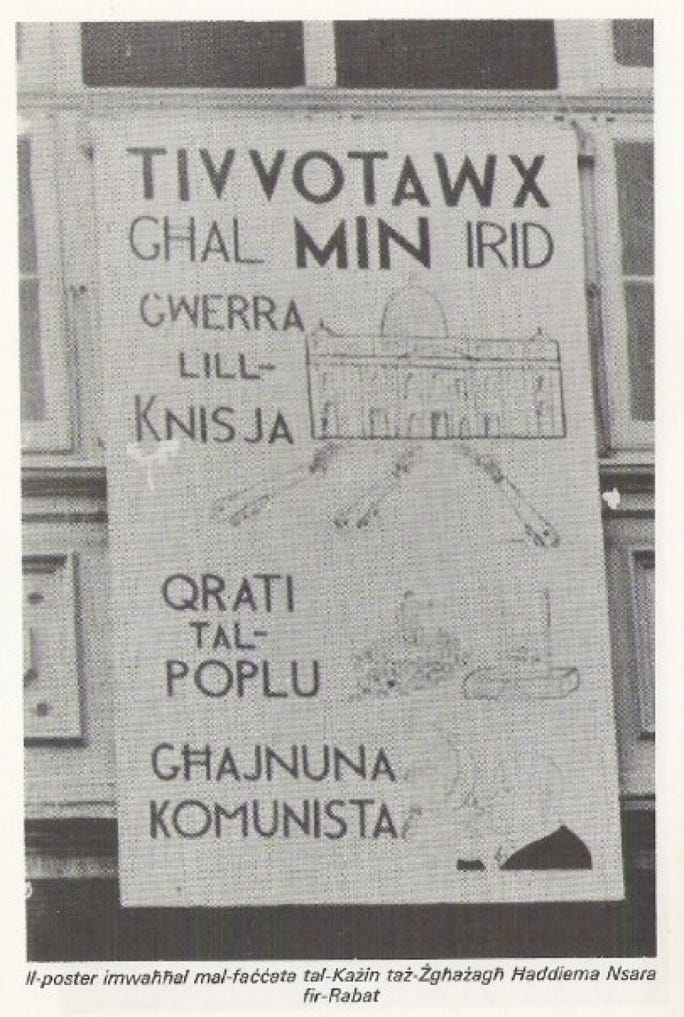

Gonzi took his God-given power to fifth gear with the April 1961 interdiction for the Labour executive, declaring the sale of or reading of socialist newspapers, as well as attendance at Labour meetings, mortal sins; as was the act of voting for the Labour party in the 1962 general elections (the Church had a year earlier interdicted Lorry Sant and Joe Camilleri as editors of the Labour youth organ The Struggle in April 1960, ostensibly over a letter penned by the pseudonym ‘John Rizzo’ – who in reality was Camilleri, Mintoff’s later right-hand man – for insulting the Archdiocese).

The Ġunta exhorted the Catholic faithful to see the forthcoming 1962 elections as a crusade against the ‘Mintoffian devils’, with socialism pitched as the sheep’s clothing for the wolf of godless communism – a “dragon”, to be faithful to the wording of the Ġunta’s Alla Magħna u Rbaħna. The Nationalist Party went on to win the election, no doubt aided in part by the fear of those who wanted to avoid mortal sin by voting for Labour.

Psychological warfare

Malta was plunged into unprecedented tribalism, with faith and sin weaponised for Gonzi’s own judgement of the living and the dead, in an island crippled by the unspoken rules of honour and shame, but also poverty and ignorance. The former Labour deputy prime minister Ġuże Ellul Mercer (disclaimer: he was the brother to my grandmother Rita Vella) was one of some seven interdicted citizens who, having died during the 1962-1969 period, was buried in the unconsecrated part of the Addolorata cemetery. He was denied a Catholic funeral, with his brother, Franciscan priest Frank Ellul Mercer, allowed to administer some sort of prayer at his grave.

Far from being a generational wound that spurred some sort of political radicalism, the punishment was humiliation for a non-partisan family that was politically anything but engaged. In my experience as a child, rarely was Ellul Mercer’s ordeal spoken about, if always respectfully. And by that time, whatever loyalty to Labour might have once existed had long been extinguished in the 1980s.

I have always seen the matter differently, and only through the lens of history: Malta’s Catholic Church has historically aligned itself against all progressive forces (and still does in the main), keen on holding on to its vast landholdings, a clericalism that controls the pious, and which has used the flames of damnation to carry out its own judgement on enemies such as Gerald Strickland, or Dom Mintoff.

Church officials in Malta today want to play down the interdiction, as some kind of Russian roulette gone wrong for a few souls whose remains are now in a cemetery that was also blessed, by way of apology, by Mgr Charles Scicluna.

But this was no banal experience for the people who silently had to endure what was Gonzi’s own class warfare against Labour voters or members m, who could not function normally in a society conditioned by the influence of priests.

Here is historian Mark Camilleri writing about it (I attach a long extract):

“Losing recognition by the Church meant being ostracised from the rest of society: a society where the parish priest had to write your reference letter to be accepted for a job, where he consulted you on your sexuality, psychology, even financial affairs, many a times making sure you would well compensate the Church upon your death, and of course… provided you with political direction. The education system was run by clerics and their lackeys; parish priests could refer you to the mental health hospital at will!...

...

“The tangible results of Gonzi’s war were very immediate. Families were torn apart. Labour activists were ostracised from social organisations. Children of Labour activists and known sympathisers were bullied at school and in the villages. Priests wielded more power and Labour youths’ chances of finding jobs decreased even further, exacerbating their already miserable economic situation. This was the bleak backdrop of Independence: in the 1960s as much as 60,000 men and women had left the islands in search for work – back then comprising as much as 20% of the population.

“And here lies a very important reason why going to hell was actually much worse than it sounds today. For the oppressed and hard-working Catholic-Labourite, mired in a dire economic scenario, who struggled to make ends meet, the Catholic religion could provide some hope and light at the end of the tunnel – death at least promised a good afterlife. Now, all the hard work and lifetime devotion to Church and God mattered no longer as the Labourite was bound for damnation anyway. In other words, Gonzi took away from the most vulnerable the most important religious element of Christianity: the resilient and spiritual hope that they could one day be saved. Gonzi sent these people to hell.”

Camilleri’s eloquence on the matter captures the essence of the gravity of the Interdiction, that it should represent to us the horror of power, the consequences of its abuse, and the war on a working class and its progressive aspirations. Likewise, I find it futile having to root wholeheartedly for a monument for the memory of the Interdiction, without publicly supporting a monument to the memory of Daphne Caruana Galizia, assassinated in an act of terror which at some point clearly enjoyed the complicity of those in power inside Castille.

But the site of such a monument must perforce be a space that entreats the public to consider its meaning, and to learn from the sorrow and history it represents. Countless statues to the former British colonial masters should now be relocated away from their prime positions and maybe displayed in museums – certainly Queen Vic has overstayed her welcome – to be replaced by sensitive works of art, that put into proper perspective the contribution of the deceased to their country. This is not decoration: historical commemoration feeds our national consciousness.

All indications point towards a FASCIST-MAFIA that murdered Daphne.