He banged the drum: The story of Tony Carr, Maltese jazz percussionist who gave Donovan solid backbeat and congas

In Strait Street to Abbey Road, Cedric Vella brings to life the story of jazz drummer Tony Carr, adding an important piece of history to the canvas of Maltese music

For its dense and knotty tunes, complex and syncopated rhythms, jazz has at times been maligned as a world of snotty-nosed excellence. But no matter where one’s musical prejudices lie, unlike the global template of rock, jazz also changes with the cultural nuances it takes root in; in places far from its American home, such as Ethiopia or Armenia to name only a few.

It is hard not to be enthused, for example, by the exploits of Maltese jazz musicians in Paris, like Sandro Zerafa, now the convenor of the Malta Jazz Festival; or Oliver Degabriele’s Akalé Wubé, a Parisian band styled by 60s and 70s Ethiopian music, which brought back to the stage Girma Bèyènè, one of the most influential arrangers of the golden age of Ethiopian jazz.

And similarly, it is difficult not to be intrigued by Cedric Vella’s Strait Street to Abbey Road, which premiered on Thursday, 10 October at Spazju Kreattiv in Valletta – a documentary which not only takes viewers for a whirl around the life of its subject, Maltese jazz drummer Tony Carr, but also for a deserved insight into the roots of Maltese jazz.

Born George Caruana in 1927, Carr and his contemporaries lived through the ravages of World War II dreaming of the sound of jazz, and emerged into Strait Street hopping from one bar to the other at what was the ‘university’ of Maltese jazz – the Old Vic Music Hall, the Cairo Bar, the Cotton Club, Morning Star, Charlie’s Bar, all lined up in a stretch of red-light entertainment for the British forces. Here the young George played with Freddie Mizzi and Sammy Galea, and Jimmy Dowling’s band, together with Joe Curmi ‘il-Pusè’ and Frank ‘Bibi’ Camilleri. These were times in which bands competed for the well-turned-out audiences of the day.

Carr took inspiration from Robert ‘Juice’ Wilson, the African-American jazz violinist who, stranded in Malta with entertainer Levy Wine right at the outbreak of WWII, became established here and promulgated jazz to yet another white audience. “Juice Wilson was the best thing that ever happened to Malta,” Carr said. “A player like him, my God, he was such a player… They [Juice Wilson and Levy Wine] were the first black players we ever had in Malta and that’s where I learnt to play that style.”

The challenges for director Cedric Vella in Strait Street to Abbey Road might have been evident in the paucity of audiovisual material that features Tony Carr, who as a session musician was at the service of stars, and not necessarily in the limelight.

So the gold nuggets of footage from the BBC where Carr plays in the Ronnie Ross band, and other archives that Vella fishes out, as well photos of Carr scouring for a cowbell inside an Abbey Road studio teeming with stars like Paul McCartney and John Bonham, have a legendary quality to them.

The main interviews with the ageing Carr had already been carried out back in 2015 in London by the jazz drummer and researcher Gużè Camilleri, grandson to the legendary Bibi. After failing to secure funding for what had to be a documentary realised with Cedric Vella, Camilleri turned his research into his master’s degree in ethnomusicology. Later, the idea for the documentary resurfaced, and Vella and Camilleri managed to secure Arts Council funding.

A decade later, Vella had to use newspaper cuttings and photos, and Jimmy Grima’s 2-D illustrations, to craft the story of a man from a small island who had big dreams to make the big time in London.

In this manner, Vella artfully manages to tie up a familiar story arc of many a Maltese migrant, who like Carr had lived through the ravages of WWII, left behind the austerity of the British fortress colony, to go right to the centre of the empire, seeking adventure and a name for themselves.

Carr’s very detailed recollections and anecdotes, which narrate Strait Street apart from contributions from others like Tony Pace and Mary Rose Mallia (Carr played on ‘Songs From Malta’, with conductor Charles Camilleri), more than colour the flavour of the age.

Packing his belongings inside his kick-drum, Carr left for London in 1952. Like many who sought fortune in London, his storyline also dovetails with that of the burgeoning Maltese crime syndicate that was taking root in Soho in the fifties. His namesake was a club-owner whose boarding house had been the site of the Tommy Smithson murder in 1956 – so George took his mother Tonina’s name and shortened the ‘unpronounceable’ Caruana to make his own mark.

He knocked on doors hoping to land a job in a market already crowded with jazz musicians. His breakthrough came with international star Billy Eckstine on his European tour. “They knew when you were a good musician,” Carr says of his audition, snapped up after rapping his fingers and hands on the skins. Eckstine would go on to dub Carr “the best drum accompanist I’ve heard in Britain.”

It solidified Carr’s reputation, who by the 1960s was engaged by pianist and arranger John Cameron to perform alongside Donovan, and later Ella Fitzgerald, Alan Price, Sixto Rodriguez, and then Madness, the Alan Parsons Project, Bryan Ferry, Roy Harper, Hot Chocolate, and Racing Cars amongst others.

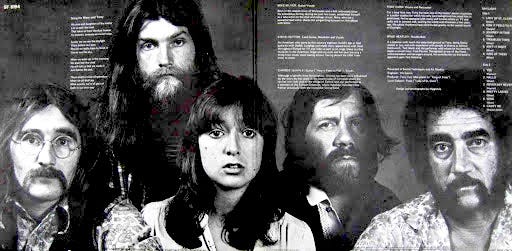

For years Carr was part of Donovan’s backing band, and the British blues outfit Collective Consciousness Society – Alexis Korner and Peter Thorup – with whom he played in three top hits. Donovan’s Sunshine Superman would reach No.1 in the United States 1966 – the guitarist on the track was then a young Jimmy Page, yet to form Led Zeppelin three years later. But Carr was in this very constellation of in-demand session players like Page and bassist John Paul Jones, his days spent driving from one studio to the other.

In 1978 he is in Paul McCartney’s ‘Rockestra’ session at Abbey Road, where Carr finds himself in the company of Pete Townshend, Hank Marvin, Dave Gilmour, John Paul Jones, Ronnie Lane, Kenney Jones, John Bonham, Speedy Acquaye, and others. In 1979, Carr plays the Concert for Kampuchea, with Wings, the Clash, Elvis Costello, Ian Dury, Queen, and the Who.

It beggars belief as to how Carr’s name only gets to enjoy wider recognition in Malta decades since his latter exploits, thanks to Camilleri’s research and Vella’s work. Sometimes, we do not even know ourselves; but it is reassuring that this legacy has been committed to historical record.