KMB festschrift: Labour PM with ‘little political nous’ cradled Mintoffianism to its death

In saving the sullied legacy of his difficult premiership, SKS toasts the loyalty of Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici to the socialist ideal. His critics too are on this festschrift, with a truth of their own

No surprises that when Labour’s publishing arm, the redoubtable Sensiela Kotba Soċjalisti, publishes a festschrift to honour a late party leader, the accolades come in thick and fast. For Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici, the hand-picked successor burdened with Mintoffianism’s ‘years of lead’ – harshly derided by critics, tarnished for presiding over political thuggery and ham-fisted educational reforms – the verdict jaggedly cuts both ways.

In the last phase of the 1980s, Labour had been ushering in a slowly recovering economy and the growth of a new middle-class. But the blight of the Church schools’ closure, the bombs and political murders, consumer spending restrictions and infrastructural failures, seem to be all that’s left of the age’s historical memory.

As the contents page to Karmenu, Il-Verità, Xejn Anqas Mill-Verità immediately reveal, those who worked under him have a different story to tell: “sincere”, “humane”, a “Christian socialist” and a “Samaritan”, and a “defender of the defenceless”. To wit, the critical reader might be immediately drawn to the less hagiographic of the 24 contributions from former Labour party officials, thinkers, and learned colleagues from the other side of the divide.

Publisher Joe Borg takes note of this cornucopia of adjectives: what to say of KMB and those who accuse him of having stewarded the violence of Labour thugs in the 1980s?

Former Labour leader Alfred Sant has already insisted this unfair legacy ignores a nefarious role played by the freelancing Dom Mintoff; the philosopher Mark Montebello and public intellectual John Baldacchino believe KMB was eternally sullied, unfairly, by the feedback loop of Labour and Nationalist violence; and Labour grandees say KMB was the antithesis of violence, accusing Eddie Fenech Adami of being egregiously dishonest in once dubbing him “the most corrupt leader” of all time.

Two friends, two enemies

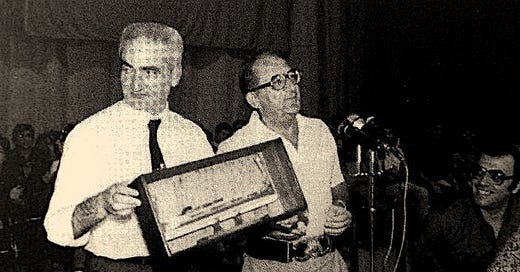

Readers are instantly alerted to the adversarial relationship of two former friends: KMB and Fenech Adami, elected in 1987 at the end of the harrowing Mifsud Bonnici premiership.

The human rights judge Giovanni Bonello, who clashed with fellow Lyceum alum Mifsud Bonnici head-on in the 1980s, remembers the two men from their law course days, laying out the non-hedonistic traits of these future prime ministers: both not entirely gregarious types, no close friends, taciturn swots who did not smoke, drink, show interest in girls, indulge in frivolity, or care about sports (yet Ray Mangion’s biography says KMB played defence for the Żgħażagħ Ħaddiema Nsara, and Joe Mifsud says KMB was a Torino supporter). They did not hang around with the other law students on Strada San Paolo – both EFA and KMB were at one time active together within the Secretariat for Catholic Action and the Malta Social Catholic Guild.

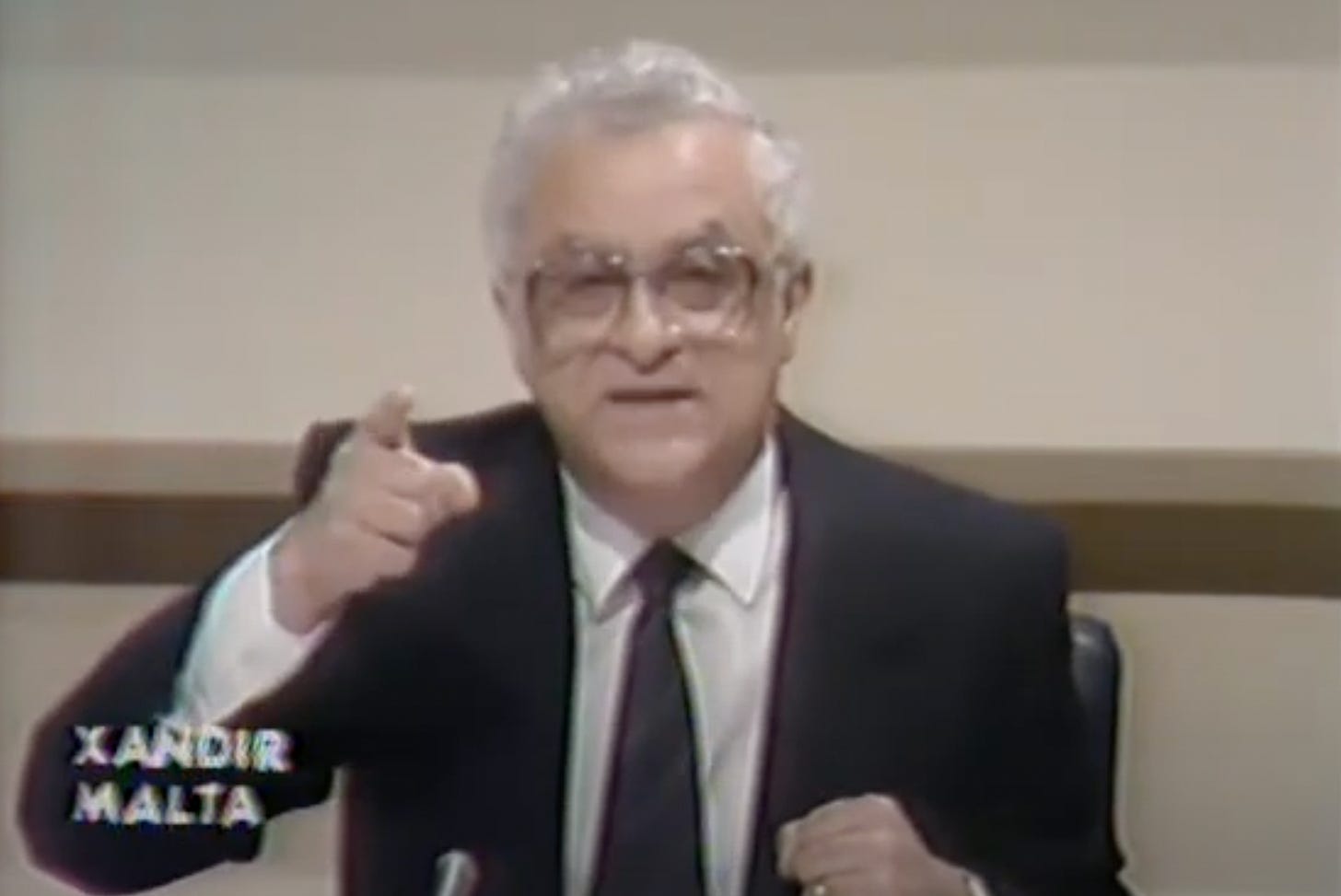

But then, while EFA charted a common political path for so many Christian-democrats, at Damascus the abstemious KMB betrothed himself to the proletariat. He became a Maltese Robespierre, Bonello declares of the flawed premier, “almost becoming Papa Doc” and then “a saintly idealist, prisoner of the populist cage.”

Knowing just about enough of KMB’s lighter side from his salad days, by the 1980s the two men were at personal odds with each other. In 170 cases, Bonello challenged Labour’s administrative and human rights violations; KMB personally, a prime minister decked in his lawyer’s toga, would defend his own laws. “He bizarrely claimed the Church was ‘not a person’ so, since the Constitution protected human rights, the government was entitled to seize its assets.”

Bonello accuses KMB of being just one step away from being a dictator, while he was styled an enemy of the working-class. “For all of his gentle manners, the elegant culture he possessed, and his compassion, he was still an inspiration and a shield for gangsters, the corrupt, and the violent,” Bonello says of KMB’s mob-like entourage.

“He was personally honest, incorruptible, blind. I once told him, ‘Karm, you would simply condemn me to death.’ He solemnly replied, ‘yes’ – just as his political intransigence condemned the 58 Egyptair passengers to death in 1985, the worst disaster of its kind, brought about by his fanaticism.”

You can almost perceive an earnest wispiness in that dispassionate ‘yes’, the same voice that would have described his former Catholic Action friend, Eddie Fenech Adami, as “a liar” in an interview with Georg Sapiano.

In the early 90s, Sapiano, him of Nationalist stock, joined the law practice of the freshly resigned Labour leader; KMB was an old acquaintance of his father from the Central Bank. Sapiano discovered the gentler side of ‘Robespierre’, as well as his ascetic ways – he took no payment for his legal services because he was living off the State’s pension. Years later Sapiano interviewed KMB, who could offer only a terse, uncompromising one-word description for his former political adversary. “It was the only moment of uncomfortable silence. As I write this now, 30 years later, I realise my question had been too personal and that I should have never asked it. Today I know what it feels like to lose a friend like that – I think I had put my finger on an open wound.”

In this intimate portrait of the unlikeliest of friendships, Sapiano points out KMB’s refusal of a state funeral, a natural corollary for someone who had apparently reneged on the prestige of his family name to “climb down the social ladder” and elevate those who were in the mire.

Christian-socialist firebrand

Many then can agree, as Mario Vella points out, that KMB had a Janus-like quality to him: gentle, humble, somewhat shy, and generous, but then entirely paradoxical in the political persona of the future prime minister.

His drift into socialism would have been somewhat enabled by the intellectualism of Fr Peter Serracino Inglott, also a friend and future confidant to Fenech Adami. PSI believed the ŻĦN’s (Young Christian Workers) ‘anti-communist’ clash with Mintoff was ill-advised and counter-productive. Both him and KMB sought to cultivate a different consciousness that attracted the working-class to the ŻĦN, but this put them on a collision course with the influential cleric Prof. Renato Cirillo.

PSI sought out the counsel of founder Joseph Cardijn, the Belgian cardinal, who advised against factionalism inside ŻĦN. When in 1961 Cardijn was invited by Archbishop Michael Gonzi to address the Maltese, the Belgian prelate warned against the Church taking up battles with the working class. Cardijn was to become a reference point for the young KMB, who back then was still promulgating the Catholic junta’s damnation of Mintoffianism.

Perhaps, Mario Vella writes, KMB met the working class inside the ŻĦN. And then he rode on to Damascus, specifically via the London School of Economics where his socialism would have come into shape, delivering him to the General Workers Union upon his return home in 1969, to fight against the Nationalist’s government’s anti-strike laws, together with Dom Mintoff.

Shaped by Mintoffianism

It matters little to know any individual truth about a man – everybody has their own version of Karmenu and the memory of the administration he stewarded from 1984 onwards.

So it is only the circumstances that turned KMB into prime minister that can surely carve out the real picture of the persona.

Mintoff despised the ‘perverse’ electoral result that gave Labour power by a majority of electoral seats and not votes in 1981; his Cabinet opposed an early election with Constitutional amendments to the electoral law before the end of the standard five-year term: “Maybe that’s when Mintoff thought he should crown a successor who could guarantee continuity for his socialism, and keep the party united,” Mario Vella, former PL president, writes.

Not the corrupt Lorry Sant with his ambition for power. Mintoff instead had the Labour general conference designate KMB as his successor, a sheer tactic meant to stem any unwelcome ambitions, recalls George Vella, President emeritus and former Labour deputy prime minister.

But by the time KMB was co-opted to the House, made education minister and deputy prime minister in 1983, the die had been already cast.

Labour’s plan for a new vocational college with a different type of graduate at MCAST, had been coupled with an assault on the University of Malta’s programme of studies, severely limiting admissions to degrees which apparently were not conducive to Malta’s needed industrial development (Mintoff wanted to dead-leg Nationalist and conservative influences in the traditional fields such as laws and the arts). It became the source of clashes with students, inspiring a mini diaspora of young men and women.

Soon, KMB’s bid to make fee-paying Church schools free of charge (“jew b’xejn jew xejn” – the battlecry that threatened a withdrawal of these schools’ licenses) was to put Labour on a historical collision course with professionals, intellectuals, and a new middle class that recoiled at the government’s heavy-handedness.

In tandem with a teachers’ strike over the dilapidated state of government schools, and the withdrawal of Church school licenses that saw secret classrooms organised inside private homes, KMB’s legacy was sealed.

“Morally, he won on principle,” Mario Vella says – today Church schools are free, in a deal with the Vatican that exchanged Church lands for the government’s annual disbursement of teachers’ salaries. “Politically he had lost it.”

And KMB kept on losing politically when dock workers ransacked the Curia; when he denied the PN a police permit to organise a political rally inside the deep-red Labour stronghold of Żejtun, which led to a street battle and tear-gas missiles from the police force; the Egyptair hijack fiasco; and with the murder of Raymond Caruana in 1986.

All the while, Dom Mintoff had been putting into shape a Constitutional deal with Fenech Adami and Guido de Marco: electoral reform, and constitutional neutrality.

KMB too enabled this endgame, ensuring the swiftest of concessions in the 1987 election.

Even the new generation that served him in the Labour executive – Alfred Sant, Marie-Louise Coleiro-Preca, Evarist Bartolo, George Vella, and Mario Vella – had stepped up to the plate by marking a definite schism from the Mintoff years. They credit KMB as having softened a transition from Mintoffian socialism to ‘Labourism’, all the while tarnished by the mayhem of the 1980s. But KMB did not kill Mintoffianism – he was its palliative nurse.

Fatal errors

Sant says KMB’s mistake was to remain beholden to Mintoff. “I knew he was critical of aspects of Mintoff’s acts… he did take steps to prevent them. But there were times where he allowed them to happen, or even supported them. It is difficult to explain why he did, unless he felt himself morally obliged towards Mintoff and to his persona and political accomplishments.”

George Vella rues KMB’s weak leadership on Tal-Barrani, an event that had the island at the cusp of a civil conflict. Vella, then a Żejtun MP, says he gave KMB the wrong advice when he suggested that the Nationalists should not be allowed to hold the Żejtun meeting in anticipation of a Labour backlash by locals. “Karmenu could have said, ‘We’ll give them the permit. If the Nationalists come to Żejtun, we tell everyone to stay put indoors. Instead there was more goading, and the rhetoric became: ‘No, they will not enter Żejtun.’ It was a senseless decision.”

KMB – the hated and loved version – was the man whom Mintoff had tasked with the epilogue to the story he started back in 1949. And in cradling this legacy, former PL president now Judge Toni Abela says that KMB’s trademark inflexibility turned him into “the most misinterpreted Samaritan in the country’s history.”

Perhaps his Christian devotion, folded into Mintoff’s socialism, had created what Mark Montebello says was a Manichean vision of politics – as had happened with the church schools question, or later the revanchist blockade of the Ark Royal: “No form of personal gain, be it private or national, was a criteria to bend principle. He was truly Manichean: either black or white, yes or no. Anything else was the devil’s work.”

George Vella agrees. “He lacked political nous. Karmenu would take the route he chose to when he was convinced he was right – but the political world does not work that way.”