Migration fear debunking 1. Malta has a low number of asylum claims

From 2021: Malta’s asylum claims are so low, it is clear that Africans are scapegoated over frustrations with foreign labourers, many working in lower-paid public services

Why is immigration such an emotive issue for the Maltese? And why is the State absent when large groups of people are delegitimised by communities which are left to deteriorate or suffer the adverse consequences of rapid influxes?

Malta is a country governed by a centre-left government whose free market embrace has not come at the expense of the welfare programme – it increased pensions, it gradually increased minimum wage, it reduced energy bills, removed exam fees, pays for free childcare and school transport, amongst many such universal services and welfare payments.

In spite of the robust economy and near full employment, the Maltese still rate immigration as one of their major concerns – especially Labour voters.

A MaltaToday survey alone rated immigration the top concern (14.2%), down by half from 32% in November 2019. But it was a major concern for Labour voters (18.3%) and those living in the south (almost 19%). NOTE: surveys since then last done in February 2023 still make it out to be a ‘Labour’ problem.

Some of these concerns are related to direct living impacts: for example, people who live in proximity to migrant communities in Hamrun, Marsa, Hal Safi or Birzebbuga. Their experience as neighbours of foreign nationals is different to those whose encounter with African migrants in Malta tends to be as consumers or recipients of public services, such as garbage collection. The communal experience in these towns can be aggravated in areas where migrants are unemployed, exploited by the construction and other industries, live in crowded apartments where rents are low, are driven to criminality by a precarious existence, or have mental health problems.

But Malta’s racism problem is spoken about less than its immigration “problem”.

African migrants rank the lowest in our perception of foreigners: we say little to nothing about legal workers from the East of Europe or Asia because we accept them as valid candidates for jobs the Maltese no longer seem available to do – such as in nursing or caring, or in catering and hospitality among many others, or driving buses and serving as take-away food; even Syrian refugees are hailed for their construction skills: they seem to be in high esteem for their skills.

It is black migrants who have it worse, and that’s because they are starting from a position of illegality: not all of them qualify for asylum when they arrive to Malta by sea, which makes a sizeable portion of migrants legally ‘unwanted’ and slated for removal from the country ( though this does not always happen, leaving these migrants in a kind of limbo as they navigate a world of legality - working - while actually being in a state of illegality).

What happens to this pool of usually unskilled or semi-skilled labour is that they cannot transition seamlessly into a state of legality: when they arrive to Malta they are already delegitimised. And that means that, without a proper status, they are (i) prone to being unemployed, or do temporary and ad hoc jobs for low pay; (ii) they could be homeless or living in overcrowded, cheap housing in places close to Valletta and Floriana (where police and immigration controls are located) and Hamrun and Marsa (where the migrant reception is located and is the major pick-up point for ad hoc work); and (iii) stuck in a cycle of poverty and its associated social and health problems.

Without a generous push from the State and the community, they can be hardly expected to “integrate” and that means they will always be scapegoated by a host nation that instead does not bat an eyelid on the crimes of those who rule over them, or the rich classes that acquire public land at a pittance.

Reality about numbers

Let’s talk about the numbers: how much is too much for Malta?

The emergency of irregular migrant arrivals is not artificial. A government source says the number of migrants residing in reception facilities (both closed and open) is over 3,500 – half of which arrived just in 2020. The Agency for the Welfare of Asylum Seekers (AWAS) also supports an additional 720 migrants through public-private collaborative projects.

2019 was already a record year for migrant arrivals by boat in Malta: 3,405 – the second highest was 2,775 in 2008, the year before Silvio Berlusconi paid Muammar Gaddafi €5 billion to stop boat departures. It ‘worked’ in 2010... just 47 arrived in Malta. Then war broke out in Libya, and the numbers went back up. After the 2013 Lampedusa tragedy, the Mare Nostrum operation rescued hundreds of thousands to Italy, and Malta’s arrivals were negligible till 2018.

These numbers are problematic for a host of services - army, detention services, social workers, asylum reception centres, and asylum determination officers - who are tasked to rescue/welcome/tend to/process asylum seekers.

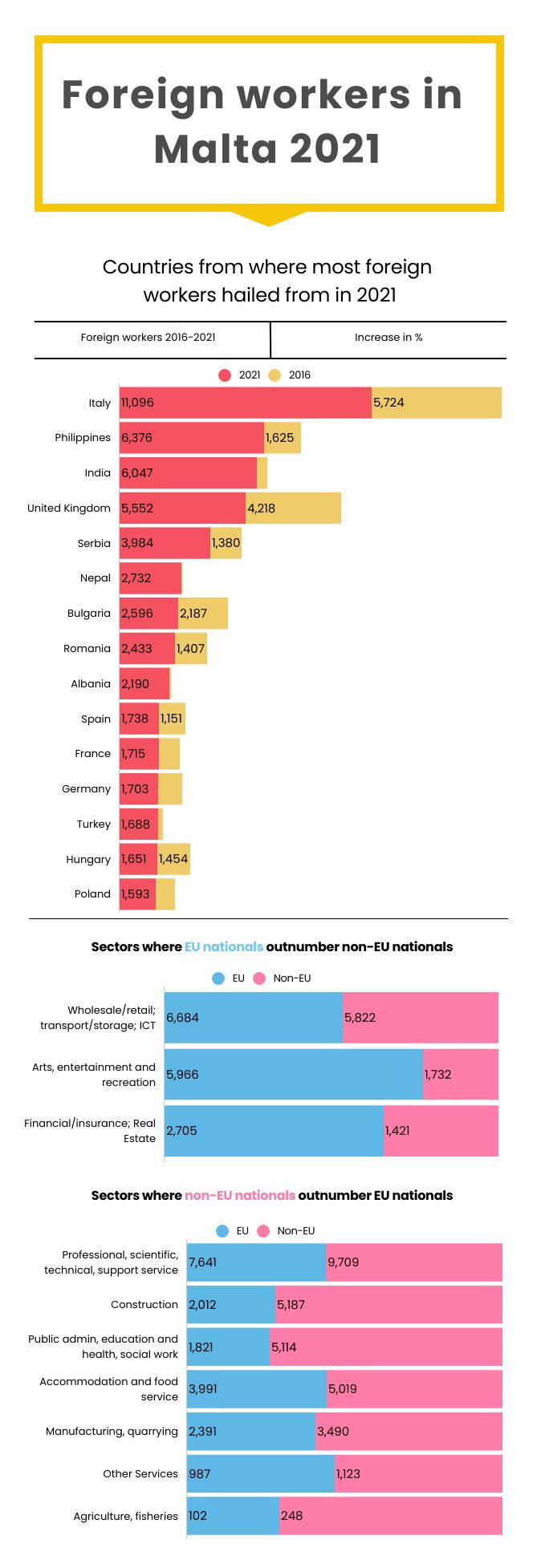

Of less concern are foreigners whose legality does not create an obligation on the State and community… irrespectively of how many thousands flow into Malta, to the consternation of nobody it seems. From 2011 onwards, foreign workers in Malta increased from around 13,000 to 67,500 (31,000 are non-EU nationals) – year on year, this was an average growth of 5,800 new foreign workers a year from both EU and non-EU. (UPDATE: The non-EU cohort shot up after COVID when many EU nationals left Malta).

The biggest non-EU groups are Filipinos (5,300), Serbians (4,600) and Indians (4,300). The largest EU group is Italian (10,000). Nobody complains much about Italian café-owners and pastry-makers, Filipino nurses and nannies, Serbian contractors and Indian bus drivers. Certainly nothing that warrants their annihilation as some egregious social media antagonists say.

The non-EU or Third Country Nationals (TCNs) are clearly filling particular labour gaps in Malta: the majority, 8,800 are in support service jobs, while the rest are mainly in construction (4,100) and retail (4,000) or nursing and caring (3,700). Within these types of jobs, few of them occupy high-level positions: they are mainly in elementary positions (10,000) or sales workers (6,800).

To the contrary, EU workers are mainly managers (5,000), professionals (6,400), technicians (5,300) or support workers (7,400).

Here you see the difference between these legal workers: EU, usually skilled workers, come for major desk jobs; the TCNs do lower-end, though extremely useful, jobs and heavy lifting.

It seems here that our social pact with these tens of thousands of foreign workers is clear: they pay taxes and rent. If they stay on for 20 years, maybe they will get to be citizens.

Is it crime and security the Maltese are worried about?

The Maltese tend to be particularly vocal about foreigners’ crimes, which is why Paceville brawls between Eastern European staff and Syrian clubbers conjure up images of a “jungle”; or crimes by Africans are met with a clamour for deportation orders. (UPDATE See how home affairs minister Byron Camilleri and PN shadow minister Joe Giglio responded in 2022 to a brawl in Hamrun between Syrian nationals). The reaction is to placate these calls with some form of banishment from the country. However it does little to address the reality of other criminality amongst down-and-out and homeless migrants (and a lot of anti-social behaviour in these two examples is carried out between/by communities who do not entirely lack agency in the communities they live… many of them are gainfully employed).

There is no question that in the towns that host the largest communities of African migrants, there are serious complaints of anti-social behaviour, criminality and security.

When such people are “delegitimised” upon arriving to Malta, there is no case for a social pact with them.

Delegitimised, because these are not workers answering job calls on LinkedIn. They depart Libya through the organisation of a criminal enterprise; their rescue at sea does not come with open arms, because European states refuse to save migrants due to populist anxieties on opinion polls and electoral results; the politicisation of NGOs who are challenging this normalisation of non-rescue, is used to justify populist anxieties (‘if the State leaves them to die, why are these NGOs not allowing us to leave them die?’).

In this state of emergency the migrants become further delegitimised by the logistical headache that their rescue - mandated though it is by international law and human rights - puts on a host of government agencies. For these visa-less, unwanted migrants, illegal entry is necessary; to the host state, it is disorderly, undeserving and intrusive.

There is also a reality many critics enjoy latching on to. That many asylum claimants might not be refugees, but simply ‘economic migrants’… much like the EU workers and TCNs who work here, except that irregular migrants come “uninvited” and with no documents in hand.

How many refugees and other migrants from Africa?

In the record 2019 year, when over 3,400 were brought into Malta, over 4,000 asylum claims were filed. But that year the Maltese agency for international protection (the refugee commission) only managed to process just over 1,000. Of these, 633 (60%) were rejected – technically, these people are handed a deportation order, which however is hard to carry out due to the lack of documentation and bureaucratic complications with the country of return.

The highest form of protection (refugee status) was given to 48 people; globally thousands upon thousands of refugees are displaced within their own countries or in neighbouring states, and the few that make it to Malta have very particular cases of proven persecution back home.

Another 359 were given subsidiary protection, which gets renewed every three years and only until such time these people can return safely to their country of origin.

And historically this is the picture of asylum in Malta: every year in the last 12 years, the islands gave refugee protection, on average, to 100 people; subsidiary protection to 963 people a year; and rejections to 520 people every year.

Deporting rejected asylum seekers instantly might go some way in placating a certain ‘anti-immigrant’ anger.

But it will not stop this racism manifesting itself to Africans in Malta whose education status, lack of skills, or poverty, and the psychological problems these bring, makes it impossible for them to enter a state of “legitimacy” through legal work, decent pay and housing.

How many still in Malta?

What we might not know for sure is how many asylum seekers are in Malta.

Since 2008 we had a total of 12,700 granted some form of protection, and 6,200 asylum claims rejected. But then you have to subtract the number of people resettled to the United States, 3,000, and those to the EU, 1,548.

Historically, it could mean that as many as 15,000 of migrants who arrived in Malta illegally are living here. The data from the 2004-2007 period is not included here.

However, Jobsplus records have only 3,173 asylum seekers and asylum beneficiaries in gainful employment as at 2019. These are not just refugees or people with subsidiary protection - they probably include rejected asylum seekers.

The government has never tracked the movements of these migrants, of which many attempt to leave and enter the EU through false documents. Is Malta still hosting another 12,000 migrants, all somehow part of the black job market, who have never left the island to move on to the EU? Not impossible, but somehow not entirely plausible.

The Maltese claim that the African underclass is a threat, if not ‘culturally’, then economically. But Jobplus numbers disprove that: in 2019, those who hailed from the sub-Sahara who were in employment were Eritreans (338), Nigerians (415), Somali (407), and Ethiopians (147) - 1,307. That is hardly job-stealing figures.

The Maltese just seem less preoccupied with those who require no dependence on the State (although legal workers in Malta get free healthcare and education): certainly culture and even race play a part in this affinity.

But when we see these numbers, the dystopian future presented by Maltese far-rightists and racists is clearly untrue. There are no numbers which suggest Malta will be “overtaken” by Somalis, Eritreans or Sudanese – technically, we are more likely to be overtaken by Italian café-owners and English “ex-pats”.

Foreign workers grow by 5,000 every year

The comparison is easy to make: since 2008-9, foreign workers grew by 5,000 each year on average; asylum claims grew by 1,500 each year on average. The latter class is delegitimised by illegal entry, arrives and stays in poverty, and is then condemned by racism to be stuck in various forms of precarity.

But immigration does matter. And governments that do not give in to right-wing anxieties must still counter concerns on immigration, and confront the problem it faces.

MaltaToday surveys on concerns reflect similar concerns in Europe where immigration remains one of the most important issues facing their countries.

However, far-right groups claiming that immigration changes their country or their culture ignore the fact that Maltese businesses have a huge demand for cheap labour that the Maltese will no longer supply. Instead of addressing the effects of unbridled development on their quality of life, immigrants are easy scapegoats because of otherwise valid problems of bad neighbourliness or social precarity.

But these problems must be addressed by police and the State’s social agencies. That is their job.

The economic concerns are certainly overstated. Elementary and unskilled jobs are occupied by non-EU workers, as the data shows. Maltese workers in low-skill jobs are finding competition from legal workers, or in the case of tradesmen, even from EU-based small business owners who expand in Malta.

But in times of COVID-19 uncertainty, where jobs will be lost, citizens are likely to be resentful of newcomers “jumping the queue” or strangers requesting asylum.

Certainly, a big part of this response is tied to the way public services are designed to cater for migrant arrivals. When reception centres and AFM maritime rescue efforts are overwhelmed by large numbers, the “emergency” perception will be felt strongly by citizens, especially those communities who live closest to these people, or who fear job competition in any shape of form.

Addressing social problems in immigrant communities and the material concerns of their host neighbours is a duty of the State, a serious challenge to be seen to actively.

Because when these complaints are communicated, especially on social media by ‘Ryan Fenech’ videos or the angry, far-right rants of zookeeper Anton Cutajar, the response becomes problematic: they are in the first place, dangerous expressions of incitement, because these “emotive” interlocutors also have incorrect views on migration.

But it is a mistake to assume an ‘elitist’ stance by calling the outbursts “backward”.

We do need experts entering the fray. And that will mean an entire host of new communicators, who are not only busy working with migrants; but also with the communities that host them.

Addressing the concerns of those who resent African migration and the social problems it brings does not mean normalising racism. But it is certainly a challenge for both State and parties. The government which does not address security concerns inside towns with both police and social workers is allowing citizens to shoulder the burden that comes from irregular migration; and a political party which does not provide a response on immigration that is positive and unique, only gives in to the scaremongering of the far-right.