Is European rearmament the path to security, or a fantasy with no basis in reality?

A reality-check on European capabilities and fragmentation underscores the need for the EU to double down on peace and humanitarianism

Europe is a fantastic peace project that often struggles to put forward a united front in the face of the disagreements and fragmentation from 27 different governments that are themselves subject to the whims of their own individual electoral cycles.

The need for a zealous European political class and bureaucrats has been essential to drive forward this shared geopolitical project of Enlightenment values, even though in many respects it could never jettison its own member states’ colonialist hypocrisies and frontier racialism, the jagged edges of their globalist missions for liberal-democracy and human rights.

Today we are seeing a different side of this zeal: the rallying words of Ursula von der Leyen, a former German defence minister, and Roberta Metsola, a Maltese politician who has no country at stake in the war in Ukraine (save for an ambitious campaign of self-aggrandisement) are calling on EU member states to spend billions on rearmament and military aid for Ukraine in the protracted war against the illegal Russian invasion.

Yet they do not tell Europeans of the structural inability of the EU to actually carry out any unified military deterrent against Russia, nor do they consider that locking Ukraine further into this war of attrition, with Europeans paying for it, is a recipe for disaster - a bill Von der Leyen surely won’t be picking up any sooner.

Even after each individual EU state spends the fabled €650 billion on their individual national armies (and another €150 billion in additional loans) – Europe will still not be a state, having no unified foreign policy, and no European army to present a credible deterrent against Russian nuclear power.

So is ReArm Europe simply a collective fantasy, the product of this esconced elite drunkenly holding on to the flickering streetlight of European unity? Do they not realise that they are opening the doors of the European project of peace to the approaching far-right phalanx of scapegoating nationalists and russophile xenophobes, by diverting €800 billion away from social and development spending, into building national defence systems?

Do they really believe that a formula of military deficits and austerity for Europeans, is the way forward for Europe?

Do we just forget that less than a decade ago, Europe was unapologetically merciless with the profligate Greeks, yet now it suspends Maastricht deficit limits to throw cash right into the arms manufacturers’ pockets? And still, the lily-livered Europe of Von der Leyen and Metsola plans for rearmament as the United States decouples itself to play its game of great powers. Instead of condemning the US-backed Israeli genocide of Palestinians (issuing only powerless sanctions against individual settlers who knock down EU-funded infrastructure in occupied Palestine but never against the Israeli state, and raising no protest at the Israeli refusal of MEPs on oversight missions), Europe stays silent.

Whatever we might think of our EU leaders, as voters we should be asking ourselves the following questions:

Will added defence spending help Ukraine effectively in a long war of attrition?

Are EU member states actually going to choose to start spending more on defence?

Do they really think a deterrent is needed against a Russian plan to invade Europe?

Does European fragmentation make such a deterrent feasible or possible?

Does ReArm actually help Ukraine?

The ReArm Europe plan is not creating some unified European defence structure.

What it does is to allow individual member states to spend more on their armies, without triggering the Excessive Deficit Procedure. The Commission wants to encourage each of the 27 member states to increase defence spending by 1.5% of their GDPs – some €650 billion over four years – but when they do, that spending will not be accounted for in terms of the Stability & Growth Pact (which mandates deficits to be kept at less than 3% of GDP).

Another €150 billion of EU-issued bonds will be lent to member states at low interest rates and long repayment terms. But again, the cash goes to national armies. “Of course,” as Von der Leyen says in her communiqué, “with this equipment, Member States can massively step up their support to Ukraine. So, immediate military equipment for Ukraine. This approach of joint procurement will also reduce costs, reduce fragmentation increase interoperability and strengthen our defence industrial base.”

Joint procurement is key: otherwise this spending will hardly reduce costs.

If each country finances its own defence industry in isolation, it is only intensifying the fragmentation of the individual European military infrastructure. Again, this is not funding a European army – but individual armies; because none of the 27 member states will be ceding their sovereignty towards any EU army (which has to be underpinned by a common foreign policy, and therefore a federal state).

Adding insult to injury, ReArm could allow member states to divert Cohesion funds (the EU cash that is used to fund higher standards of living and equalisation of educational, healthcare and social structures across Europe) for defence, further punishing local populations for the pipe-dream of ‘rearmament’.

You are left with, theoretically, 27 armies, each procuring their preferred technologies and suppliers – which also comes with interoperability issues: each army has their own brands of jet fighters or tanks (some countries have multiple suppliers of the same type of weaponry); so whenever they send whichever armaments to Ukraine, this also requires training Ukrainian personnel to handle those specific armaments.

A 2017 paper by Federica Mogherini (former HRVP) estimated that in the EU there were 178 different types of military equipment, against just 30 in the United States, of which 17 different types of main battle tanks, against 1 in the US, 29 types of destroyers/frigates, against 4 in the US, 20 types of fighter planes, against 6 in the US.

Unless you treat defence as a shared EU responsibility, these funds risk being spent inefficiently, leading to duplication rather than targeted, EU-wide projects.

Will EU states actually raise their defence spending?

We have to consider how each member state views the risk of Russia, currently in its third year of its illegal invasion of Ukraine, and whether this warrants increased defence spending on their part.

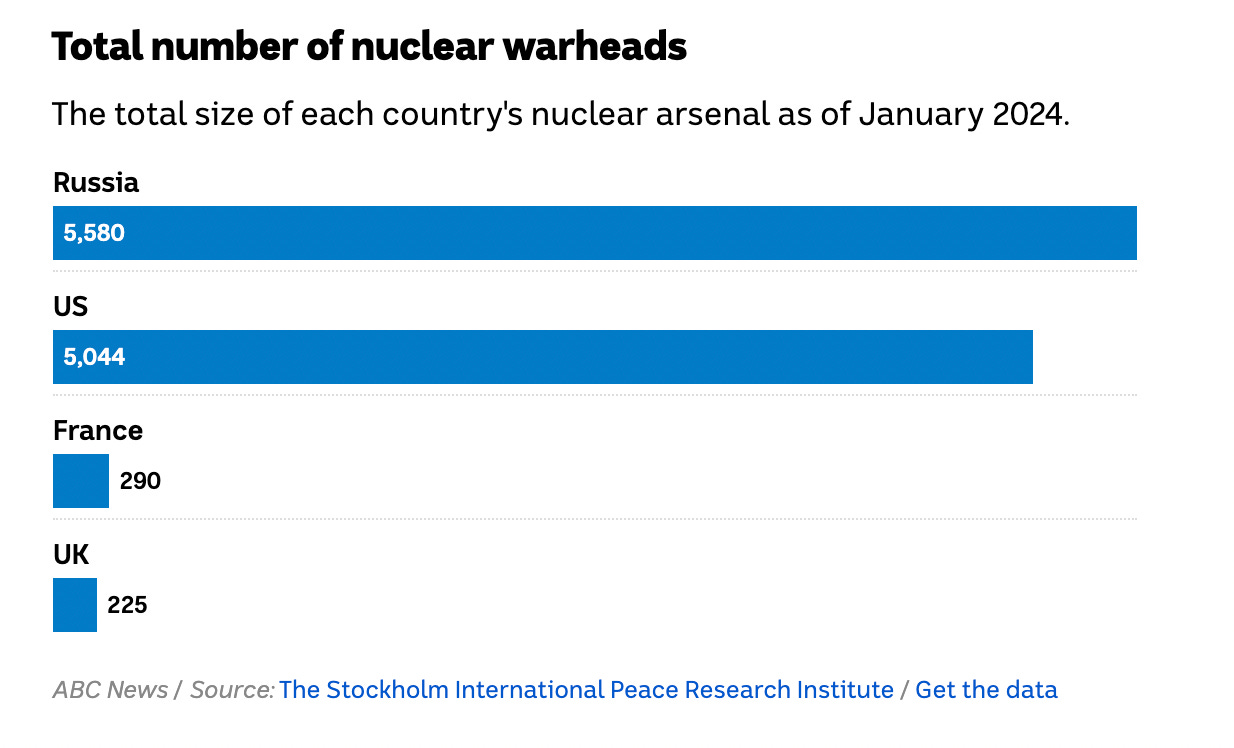

With only a very blunt assessment of the nuclear weaponry that Russia has, a good portion of individual EU member states know that the prospect of ‘rearmament’ is futile, unless Europe embarks on an intensive diplomacy project to pursue peace for Ukraine.

And because ReArm Europe does not include direct EU-level defence initiatives, once you have each member state raising cash for their own defence or military aid to Ukraine, then you are sending 27 different democracies on their own fiscal trajectories and financial disparities, created by public debt.

I mentioned Greece before because it is ironic to have someone like NATO secretary-general Mark Rutte, the former Dutch PM, once an advocate of strict budget deficits, throwing away frugality to raise military spending to 5% of GDP to meet Nato (American) demands. Italy, for example, today spends less than 2% - but you won’t find any expansionist zeal when some Keynesian spending is needed on education or social cohesion for southern EU member states. It seems that when it comes to war there are no limits on spending.

If Europe now decides to deepen its austerity policies and cut spending on welfare, healthcare, education, and research… even divert funds from the EU’s Cohesion fund, the funding that is intended to reduce social inequalities, what will the ‘About Damn Time’ crew say when fiscally weaker countries start facing social upheavals? Would not higher debt and lower social spending weaken European unity?

Is the Russian threat credible?

Malta’s prime minister Robert Abela (who seems to have very debatable views on Trump and his version of Maltese military neutrality) has suggested quite clearly that EU governments are actually divided over the reasons that prompted Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine: namely, the attempt to take Nato closer to the Russian border, which threatened the principle of indivisibility of security, which Russia had long warned about.

Naturally those who live close to the Russian border, and who were unwilling vassals of the Soviet empire – Finland, the Baltics, Poland – have a different view of Putin. Former Finnish PM Alexander Stubb says Putin harbours imperialist ambitions and that he is a hater of European liberal democracy. The EU’s High Representative for external affairs Kaja Kallas is a former Estonian PM and therefore is sensitive to Russian encroachment (disinfo alert: Russia claims her appointment by the EU was intended at escalating the conflict).

But then this might also be the point at which Europe decided against any form of negotiation and diplomatic solution with Russia: Stubb himself articulated this position, stating that “peace in Ukraine can be achieved only on the battlefield.” The price was paid when no breakthrough was achieved in the 2022 peace talks: according to a New York Times analysis of those negotiations, Ukraine was willing to renounce joining Nato, but knew that equivalent security guarantees by the great powers would be hard to come by. When the Ukrainian army continued to inflict defeats on the Russians, and Western military aid was ramped up in the summer 2022, Ukraine had little further reason to talk to the Russians.

Inside the EU, what has emerged since then is a clear disparity between those that view Russia as a threat to the rest of Europe, and those who do not. It is not surprising to find that military expenditure ratios across the 27 member states are also inversely proportional to the distance of a country’s border from Russia (Cottarelli et al, OCPI).

The cost of EU military fragmentation

An interesting finding in the Cottarelli report is that defence spending in the EU is not only much lower than in the United States (as a ratio to GDP), but it is also biased towards salaries – that means that in terms of public spending, European armies are geared towards public employment rather than actual defence needs: “In a world in which technology reigns, having many soldiers who are more poorly armed and trained does not seem ideal.”

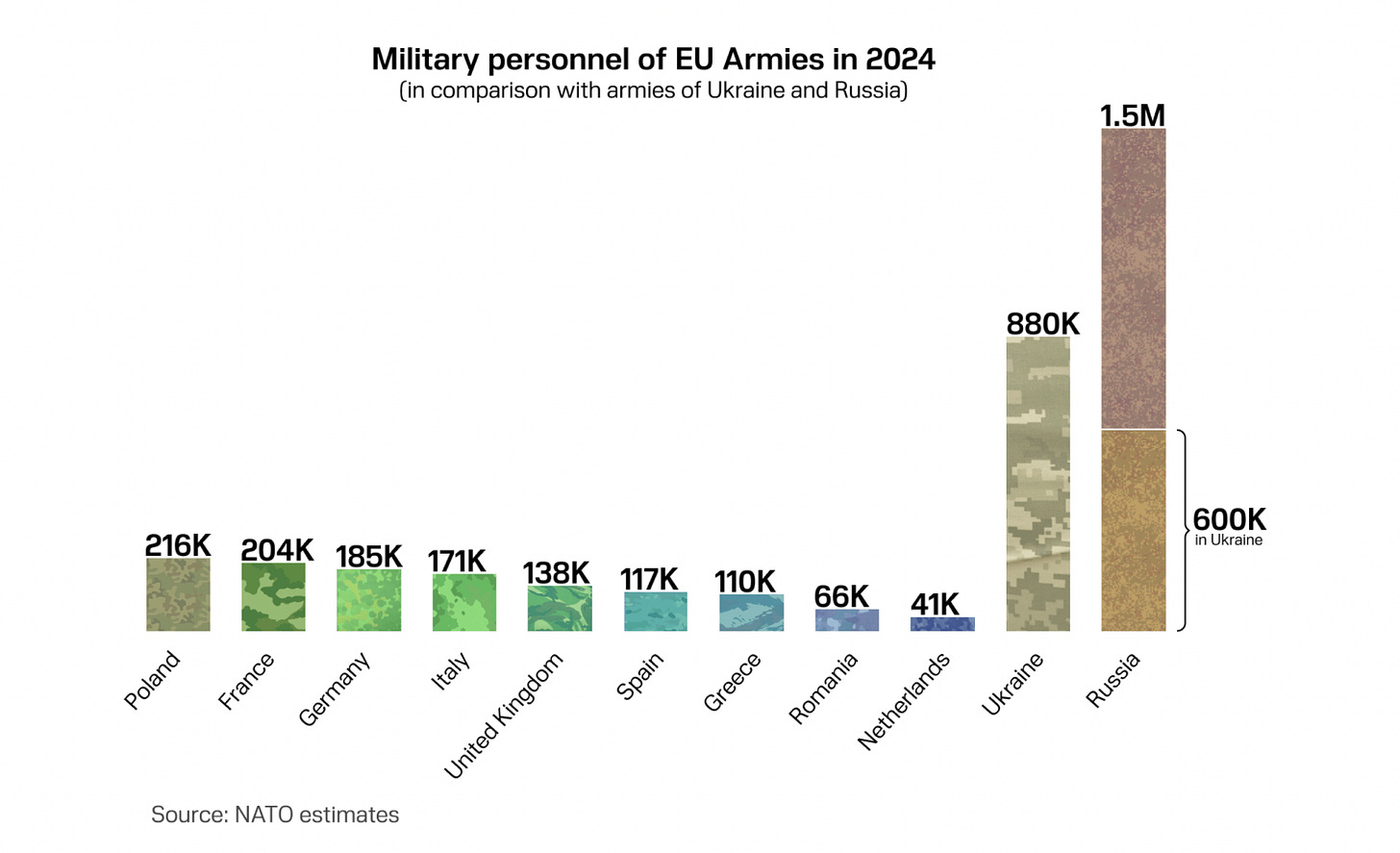

So in 2023, the combined military personnel in Europe was 1.34 million units, more or less the size of the Russian armed forces (1.32 million units). Spending for defence was some $304 billion, much more than Russia ($109 billion), although it is estimated that the gap in terms of spending reflects to a large extent the different price and salary levels in Russia and the EU.

Fragmentation is the real problem here: even when you increase spending, how do you coordinate 27 different armies from a combat standpoint, without any joint procurement of defence weaponry and technology?

Putin has it easier: he commands one army.

Secondly, is the purported EU deterrent against Russia, in the eyes of Von der Leyen, going to play out in the same way as a long war of attrition in Ukraine? Or will it be outright nuclear war in the eyes of the Russians? Because without the American nuclear deterrent, there is no response to be had against Russian’s 5,580 warheads (the only EU nuclear power is France with 290 nuclear warheads). And would France use its nuclear warheads to defend some EU state hit by a Russian nuclear attack, opening itself up to Russian military attack? Which EU member state would step up?

(UPDATE - Macron has stressed that French nuclear deterrence is ‘complete, sovereign, French from start to finish’.)

Adapt and renew the European peace project

A surge in military spending is not social progress, but a move that will punish European leadership on education, healthcare, and research. By abandoning diplomacy, international law, and multilateral institutions like the UN, the risk is that global conflict simply becomes likelier.

Peace has to be built, not ‘re-armed’.

With Trump decoupling from Europe, it is the EU that has to adapt to the new spheres of influence emerging in the world. It only seems inevitable. Without US-Nato support, Ukraine appears to be consigned to the Russian sphere of influence while Trump busies himself with laying claim to his own North American neighbours. Ukraine’s fate might be that it too will pay the price for its geographical caprice: Russian annexation in the East, while paying tribute with the American plunder of its rare earth minerals.

It’s a grim outlook.

Europe in the meantime still has €274 billion in seized Russian assets that can be the basis for an intensified diplomatic outreach.

Europe has to face up to the unpredictability of a new world order in which great powers are claiming for themselves the multipolar organisation of international relations.

Instead of threatening rearmament that gives Europeans nothing but a guarantee of austerity, it should be furthering the European peace project and investing in social welfare and the New Green Deal. It should be creating jobs, raising standards of living, and welcoming mass migration to build sustainable economies.

It should be fighting climate change, not allowing the EPP and its allies to cut back on its ambitions on top of the Trump administration’s anti-environmental agenda; it should uphold its regulatory structures by developing its own AI and social media platforms to counter American techno-hegemony, building relations with other spheres of influence that also includes China; and in Gaza, it should be organising a humanitarian relief mission that counters and condemns the US-backed Israeli genocide - it is here in the Middle East that Europe must take the spirit of the Ventotene Manifesto that dreamt up the vision of a united European people, to build peace as the basis of political unity, instead of funding the simulation of militarised power.